This is a very in-depth blog that analyzes plant protein vs animal protein and may take you some time to read as it does get into the weeds a bit. If you’re just looking for a summary, I’ve provided a TL;DR (Too Long, Didn’t Read) below.

TL;DR:

I recently got into a debate about plant protein vs animal protein. Particularly on which one was more effective for muscular development. After diving back into the research, my stance hasn’t changed. While plant proteins can be part of a healthy diet, animal proteins are simply more effective for building and maintaining muscle due to their complete amino acid profile, higher biological value, and better digestibility.

A lot of studies that claim meat is harmful rely on observational data, which can be misleading. These studies often don’t account for key variables like whether the meat consumed is high-quality or processed junk, or whether participants have other healthy or unhealthy habits. That’s why I put more weight on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that control for these variables—they’re the gold standard in nutrition research.

Bottom line: while you can definitely build muscle on a plant-based diet with careful planning, animal protein is still the more efficient and effective choice for those serious about muscular development. Exceptions like professional plant-based athletes don’t disprove the rule—most of us don’t have personal chefs or dietitians to meticulously plan our meals. If you’re looking for the most straightforward path to muscle growth, animal protein remains the best option.

Still here? Great, grab a coffee or snack, and let’s dive in. Enjoy. Avg read time is 8 minutes.

Plant Protein vs Animal Protein

I was recently involved in a lengthy argument in an online running forum about whether a vegan/vegetarian diet is better than an omnivorous diet. I love getting into these types of debates because they force me to research my own arguments once again, either to reinforce what I already knew or to possibly change my mind on a topic. This was not a topic I changed my mind on.

First off, I need to express my bias. I’m in the world of fitness, and because of this, I view muscular development as extremely high on the totem pole of factors that lead to a longer life. Muscle doesn’t just allow you to remain more agile as you age; it makes you more durable and serves as a glucose disposal system. As you exercise and move around in life, you are churning through muscle glycogen, which is basically sugar water that sits in your muscles to be utilized for fuel. When you eat carbohydrates, if you’ve been meeting your movement demands, those carbohydrates will go towards refilling those glycogen stores.

Having this powerful glucose disposal system leads to a decrease in all sorts of chronic illnesses, and so its importance cannot be overstated in my opinion. This is the lens through which I’m viewing all of this.

With that said, onto the main question of today’s blog: Is animal protein superior to plant protein?

Complete Amino Acid Profile

Proteins are made up of amino acids, and there are 20 different types that our body needs. Nine of these are essential amino acids, meaning our body cannot produce them, and they must be obtained through diet. Animal proteins, such as those found in meat, eggs, and dairy, are considered “complete” proteins. This means they contain all nine essential amino acids in the right proportions necessary for muscle repair and growth.

In contrast, most plant proteins (with the exception of quinoa, soy, and a few others) are “incomplete,” lacking one or more of the essential amino acids. This can make it more challenging to get the full range of amino acids needed for optimal muscle development from plant sources alone. There are ways of getting all of the amino acids one needs in a plant-based diet, but it requires proper planning of food combinations.

A common food that’s often touted as being high in protein is beans. The macronutrient breakdown of beans is as follows:

- Protein: 15 grams

- Fat: 1 gram

- Carbs: 45 grams

Something to notice right out of the gate is that there are three times as many carbohydrates in beans as there is protein. The reason I bring up beans is because it’s easy to remember that they need to be paired with something like rice in order to build a complete amino acid profile. So let’s look at rice:

- Protein: 7 grams

- Total fat: <1 gram

- Carbohydrates: 34 grams

So with this combination, we end up with:

- Protein: 22 grams

- Fat: ~1.5 grams

- Carbohydrates: 79 grams

Wow, that is a lot of carbohydrates. Now, if you’ve been following me for a while, you know I’m not against carbs, and I have a very high carbohydrate intake myself because of all the lifting and running I do. The average person, however, needs to be mindful of their carbohydrate intake if they are not especially active.

Now let’s look at a piece of meat. The macronutrient breakdown of a chicken breast is as follows:

- Protein: 53.4 grams

- Carbs: 0 grams

- Fat: 6.2 grams

Are you starting to get the picture? Animal protein is usually just protein, whereas plant protein, even in just small amounts, comes with a lot of other stuff, mainly in the form of carbohydrates. So, in order to properly plan for an adequate amount of protein, the pairings that are necessary will force one to sacrifice another macronutrient (usually in the form of fat) in order to stay at maintenance calories or, if they’re trying to lose weight, a calorie deficit. If someone isn’t aware of this, in an effort to consume enough protein, they will oftentimes end up gaining weight because of the excessive amount of carbohydrates they’re now consuming.

Biological Value of Plant Protein vs Animal Protein

The biological value (BV) of a protein measures how efficiently our body can use the protein we consume. Animal proteins typically have a higher BV compared to plant proteins. For instance, eggs, often referred to as the gold standard for protein, have a BV of close to 100, meaning our bodies can utilize nearly all of the protein they provide. Beef, chicken, and fish also have high BV scores, making them excellent choices for those aiming to maximize muscle gain.

Plant proteins, on the other hand, generally have lower BV scores. While combining different plant proteins can create a more complete amino acid profile, this requires careful planning and larger quantities of food, which can be challenging for those trying to build muscle.

Here’s an interesting study where they set out to compare the amino acid content of plant protein vs animal protein.

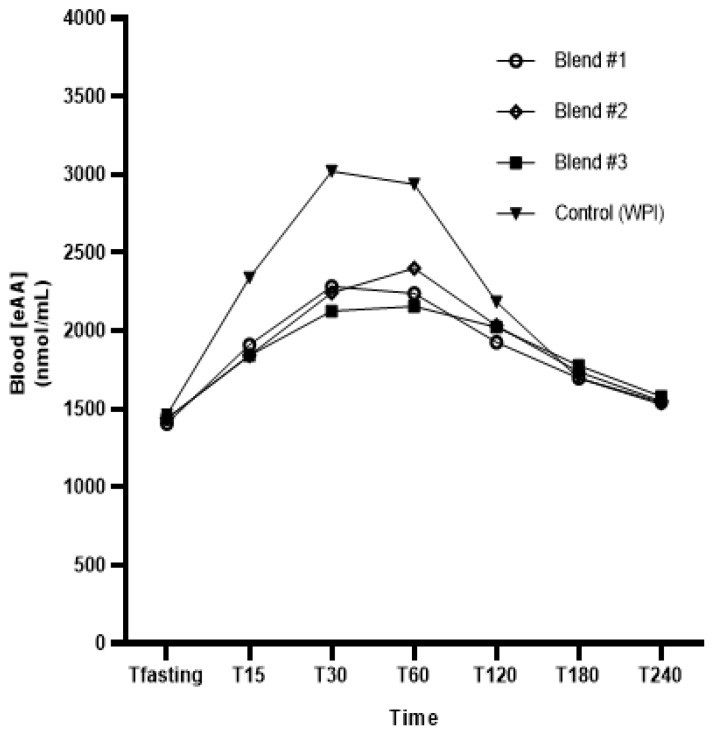

This is a good example of animal-based protein having a higher biological value because the researchers tried their best to increase the total amount of plant protein to make up for the lack of leucine content and other amino acids.

This chart from the study shows that in order to equate (make equal) leucine and the total amount of essential amino acids, the plant blends (#1-3) had to have about 40% more total protein than the whey protein group (C).

| Study Product Comparison | ||||

| #1 | #2 | #3 | C | |

| Total protein (g) for condition | 34 | 33 | 34 | 24 |

| Total leucine content (g) | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| PDCAAS | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Total eAA content (g) | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

#1 = Protein Blend #1 (Test)—Pea, Pumpkin; #2 = Protein Blend #2 (Test)—Pea, Pumpkin, Sunflower, Coconut; #3 = Protein Blend #3 (Test)—Pea, Pumpkin (hydrolysate); C = Control—Protein Isolate (WPI).

So, with them doing their best to give plant protein a fair shot (technically unfair to animal protein) you would expect to see blood concentrations of amino acids be similar across each group right?

Well, I hate to break it to you, but that was not the case. Even with them giving plant protein the upper hand, not just with trying 3 different blends, but also increasing their total amount of protein to ensure that they had the same amino acid profile and equal Leucine content. Whey protein, which was the control group, still had about a 30% higher increase in essential amino acids in the blood they measured. You can see the result down below. Not the WP had a much larger area under the curve than the other groups.

That’s a huge difference and speaks to the fact that not all protein is created equal. One of the main reasons plant proteins have a lower bioavailability, is that the protein is bound up in fibrous plant material that is difficult to digest. So, a lot of the protein get’s excreted in ones fecal matter before the body has had a chance to absorb it which happens in the small intestines with animal protein.

This is due to the simpler structure of animal proteins and the absence of certain antinutrients, such as phytates and lectins, which can be present in plant foods. These antinutrients can interfere with the digestion and absorption of protein, making plant proteins less bioavailable.

Leucine?

Now you’re probably asking, “What the heck is leucine?”

Leucine is one of the essential amino acids and plays a crucial role in muscle protein synthesis, the process your body uses to repair and build muscle tissue. Animal proteins tend to be richer in leucine compared to plant proteins. For example, 100 grams of chicken breast contains about 2.8 grams of leucine, while 100 grams of lentils contains just about 0.65 grams.

Leucine acts as a key signal to your muscles, telling them to start building and repairing. Higher leucine content in animal proteins means a stronger signal for muscle growth, making it easier to build and maintain muscle mass.

Leucine supplements are a great option for people that are having a hard time meeting their protein demands through a plant-based diet. Simply have a scoop of leucine mixed in water or whatever fluid you like with the meal that you suspect might be low, and that should cover you.

Safety Risk of Plant Protein vs Animal Protein

One last topic I want to touch on is the safety risk of plant protein vs animal protein. I feel the need to touch on this because, in an effort to redeem plant-based protein, advocates would have you believe that meat is outright bad for you and that it causes an early death. That’s just not the case and as part of a balanced diet, high quality lean meats are perfectly good for ones health.

The debate over whether meat is bad for our health is ongoing, and it’s easy to get lost in the noise of competing studies and opinions. One common claim is that meat causes high blood pressure and other health issues. However, to truly understand the impact of meat on health, it’s crucial to look beyond the headlines and dig into the details of the studies being referenced.

The Misleading Nature of Some Studies

Many studies that suggest a negative impact of meat on health are observational in nature. These types of studies, while useful for generating hypotheses, have significant limitations. Observational studies often rely on self-reported data and do not involve any intervention or control over participants’ behaviors. For example, a study might group individuals who eat meat together, but if it doesn’t differentiate between those who consume high-quality lean meats and those who frequently eat processed meats from fast-food chains, the results can be misleading.

A prime example is this meta-analysis that includes a study called the RBVD-Study. This one of many studies that are often cited to back up their plant based superiority claims.

In this study, “meat eaters” were defined as individuals consuming either three portions of meat or two portions of meat and two portions of processed meat. “Processed meat” could mean salami, sausage, Burger King, Slim Jims, and so many other terrible cuts of meat. This is a broad and vague definition that lumps together vastly different dietary patterns. Furthermore, the study did not control for critical lifestyle factors such as smoking, exercise, or overall diet quality. This lack of control allows for significant “healthy user bias,” where the negative health outcomes associated with meat consumption could actually be due to other unhealthy behaviors common among the participants who ate more meat. We know that meat eaters are more likely to smoke cigarettes, not take walks, drink soda, and have many other conflicting lifestyle factors. Alternatively, vegans/vegetarians are more likely to exercise, stay hydrated, get out in nature, do yoga, etc.

The Importance of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs)

This is why randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are considered the gold standard in nutrition research. Unlike observational studies, RCTs involve changing participants’ diets in a controlled environment, where all variables can be accounted for, including calorie intake, macronutrient balance, and overall diet quality. For instance, in an ideal study, participants would be provided with their meals to ensure that all factors are iso-calorically controlled—meaning everyone consumes the same number of calories and the same ratio of macronutrients. This eliminates confounding variables such as body weight differences, which can also influence health markers.

Without such controls, studies that link meat consumption to negative health outcomes, like high blood pressure, can be misleading. For example, if a study shows that meat eaters have higher inflammatory markers, we must ask: Are they eating high-quality lean meats or processed junk food? Are they sedentary or active? Do they smoke or live a generally healthy lifestyle? Without answering these questions, it’s impossible to draw accurate conclusions.

Epidemiology vs. Nutrition Science

It’s also important to recognize that epidemiology, the study of how diseases affect large populations, was not originally designed to answer complex nutritional questions. Especially not plant protein vs animal protein. Nutrition is highly individualized, and dietary impacts can vary widely based on a person’s overall lifestyle, genetics, and environment. The use of epidemiological studies to make broad claims about diet, especially concerning something as nuanced as meat consumption, often leads to overgeneralizations and can erode public confidence in nutrition science.

This is why critical evaluation of the studies being cited in any dietary debate is essential. Not all studies are created equal, and understanding the limitations and methodologies behind them is key to making informed decisions about your health.

The claim that meat is inherently bad for you is not as clear-cut as it may seem. Many studies fail to account for critical variables and rely on broad generalizations that can mislead the public. For anyone serious about understanding the true impact of meat on health, it’s essential to dig deeper into the research, prioritize high-quality studies like RCTs, and remain critical of sweeping statements based on flawed data. Remember, nutrition is about balance, and what works for one person may not work for another. Always look beyond the surface and seek out the full story behind the studies you read.

Conclusion

While plant proteins can certainly contribute to a healthy diet and muscular development, animal proteins offer distinct advantages that make them superior for building and maintaining muscle mass. The complete amino acid profile, higher biological value, leucine content, digestibility, and additional nutrients all make animal protein a more effective option for those serious about muscular development.

Often, someone will cite a plant-based athlete that has a great physique and say, “Well, what about them?” While many plant-based athletes successfully build muscle, they often need to consume larger amounts of protein and be more meticulous in their dietary planning to achieve the same results as someone consuming animal protein. Also, exceptions don’t disprove the rule. Professional athletes often have chefs or, at the very least, a paid professional who has given them meal plans. Again, this is not applicable to the average individual.

That said, everyone’s dietary choices are personal, and it’s possible to achieve muscle growth on a plant-based diet with careful planning. However, for those prioritizing efficiency and effectiveness in building muscle, animal protein remains the gold standard.

If you’ve made it to the end, I congratulate you on informing yourself on a very important topic that will continue to come up probably until the end of days. If you learned something, consider forwarding this blog to a friend, coworker, or loved on that you believe has been misinformed or could use some nutritional guidance.

My last blog was looking at Dr. Bergs latest viral video where he makes the claim that protein bars are worse than candy bars. I dissected this claim and wrote all about it. You can read that blog here!

Thanks for reading and I’ll catch you at the next one.

2 thoughts on “Plant Protein vs Animal Protein”

Very interesting and informative! I really enjoy your blogs. Thank you!

Thanks, I’m glad you enjoy them. I will keep writing them!

Comments are closed.